The history of the maidens of the porch of the Erechtheion, and how they became known incorrectly as 'caryatids' started with a misunderstanding with the Roman architect Vitruvius in the first century BCE.

For four hundred years, that is, while Athens was still autonomous and “Greek” the maidens of the Erechtheion were never considered "caryatids" in the humiliated, enslaved sense described by Vitruvius' opening story to his book, de Architectura. They come from a line of pre-Persian War architectonic females, such as the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, perhaps a miniaturization of the maidens that danced around the bases of the Temple of Artemis at Epheus. Nor were they considered caryatids by those who chose to copy them in their buildings in the later Classical and Hellenistic periods.

It is only with the publication of Vitruvius that this conflation took place, and Augustus’ architects working on the Forum picked up the maidens as symbols of defeat, interspersed with the clipei (shields) with heads of conquered nations - remembering, of course, that Greece had become a Greek province by then, and so the shoe now fit. Before that, nada. Augustus and his design crew were somewhat familiar with the building because the Athenians had dedicated a little monopteros to him on the Akropolis (built by Athenians, not Romans, as is often confused) which copied elements of the Erechtheion, and the Romans must have acquired a model to copy from Athens for Augustus' Forum by some means.

The Whole Story:

For the full version of this article, see: Lesk, Alexandra L. “Caryatides probantur inter pauca operum: Pliny, Vitruvius and the Semiotics of the Erechtheion Maidens at Rome,” Arethusa 40 (2007): 25-42. PDF DOCUMENT

The contemporary building accounts indicate that the Erechtheion maidens were called korai or “maidens” in the fifth century BCE..

Not once in the ancient sources are the Erechtheion maidens on the Acropolis referred to directly as "caryatids." But rather than simply dismissing every post-antique reference to the Erechtheion maidens as "caryatids" as a mistake, the origins of this conflation of terms can be examined using hermeneutics, that is, the study of their interpretation.

By following the manifestations of this conflation backwards through time, we can argue that its origins lie in the late first century B.C..

Vitruvius on the maidens

To illustrate his assertion that an architect’s knowledge should be well-rounded, Vitruvius wrote in the early 20s B.C.:

A wide knowledge of history is necessary because architects often incorporate many ornamental features in the designs of their works, for which they must be able to give a reasoned account when asked why they added them. For example, if anyone erects marble statues of robed women, which are called Caryatids, instead of columns on his building, and places mutules and crowning members above them, this is how he will explain them to enquirers: Caryae, a city in the Peloponnese, allied herself with the Persian enemy against Greece.

Later the Greeks were rid of their war by a glorious victory and made common cause and declared war on the Caryates. And so the town was captured, the males were killed and the Caryan state publicly humiliated.

The victors led the matrons away into captivity, but did not allow them to lay aside their robes or matronly ornaments. Their intention was not to lead them on one occasion in a triumph, but

to ensure that they exhibited a permanent picture of slavery, and that in the heavy mockery they suffered they should be seen to pay the penalty for their city.

So the architects of those times designed images of them for public buildings specially placed to uphold a load, so that a well-known punishment of the Caryates’ wrongdoing might be handed down to posterity.

Scholars' debate on terminology

Because of this passage and the prominence of the maidens of the Erechtheion, scholars have searched for a way to reconcile the term caryatid with these statues and the origin of female architectural supports.

Scholars usually come to one of three main conclusions on this topic:

1. The Erechtheion maidens are indeed caryatids in the Vitruvian, i.e., post-Persian punished, sense;

2. The Erechtheion maidens have nothing whatsoever to do with this medizing etiology and are instead descended from the pre-Persian female architectural supports from Delphi (e.g., the maidens on the Siphnian Treasury; cf. Plommer 1979.102); and

3. The term caryatid refers to the dancers at the shrine of Artemis Caryatis who were commemorated in stone at Delphi.

These approaches focus on whether Vitruvius’s account is trustworthy. His veracity is doubted because he offers many other appealing stories to explain, for example, the origins of the Doric and Corinthian orders; stories which are now generally regarded as having been invented by Vitruvius.

It was the eighteenth-century German antiquarian G. E. Lessing who first suggested that Vitruvius’s account of the origin of the term caryatid was a fabrication. Most scholars now summarily dismiss Vitruvius’s story of post-Persian punishment by referring to the female architectural supports from before the Persian War, such as those from the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi that date to ca. 525 b.c. There are also historical problems with Vitruvius’s account, namely that Caryae was not destroyed until after the Battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.; in other words, about a hundred years later than Vitruvius insinuated.

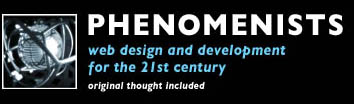

Above: reconstruction of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi. Model: John Goodinson.

It is unfortunate that, by not using a contextualized diachronic approach, scholars often make unfounded assumptions that lead to conflated interpretations. The following statements are just two recent examples:

1. “Attempts to de-emphasize the weight carried by the maidens combined with their position which isolates them from the rest of the building and obscures their architectural function would not have been introduced if these figures depicted enslaved women carrying heavy burdens, as Vitruvius would have usunderstand” (Shear 1999.84).

2. “The Roman architect Vitruvius states that the Erechtheion statues depicted the women of the Lakonian city of Karyes, which sided with the Persians during the Persian Wars . . .” (Brouskari 1997.185–86).

So what is wrong with these statements? First, both interpretations incorrectly assume Vitruvius was talking about the Erechtheion when he gives his definition of caryatid. Nowhere in Vitruvius 1.1.5 does he say he is talking about the south porch of the building known as the Erechtheion. Both scholars also ignore the fact that Vitruvius’s story requires the women to be matrons and not maidens, as they are specifically characterized in the ancient building accounts, and both ignore the fact that Vitruvius places a Doric, and not an Ionic, entablature above them. These citations serve to demonstrate the importance of a contextualized diachronic approach in assessing the relationship between Vitruvius and the Erechtheion maidens.

The initial conflation of the Vitruvian term caryatid and the Erechtheion maidens has generally, although incorrectly, been attributed to Stuart and Revett, the intrepid traveler-architects who visited Greece in the 1750s, and to Winckelmann, who never visited Greece. In fact, it was an Italian named Cornelio Magni who, in 1674, was the first early modern European traveler to call the Erechtheion maidens caryatids. In any case, the mistake these writers make might be perceived as a natural one: missing the significance of that singular term mutulos that indicates that a Doric frieze belongs above caryatids.

Post-Antique Erechtheion Maidens

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and so before these earliest travelers to Greece, it is possible, though difficult, to identify the equation of Erechtheion maiden and caryatid. On the one hand, there exist evocative Renaissance drawings of copies of the Erechtheion maidens in various collections in Italy, such as a drawing in a codex in Berlin, but such examples are not labeled as caryatids.

On the other hand, we have schematic renditions of caryatids that illustrate early modern editions of the opening passages of Vitruvius, such as the examples from the 1511 edition of Vitruvius by Fra Giacondo and the 1556 edition by Palladio and della Porta in Barbaro, that bear little to no resemblance to the Erechtheion maidens.

There is, however, monumental evidence for the Erechtheion maidens being caryatids in the eyes of Renaissance viewers in the Louvre. Jean Goujon, who studied with Michelangelo, placed four Erechtheion-inspired maidens in his tribune that holds up the musicians’ gallery in a room called in the building accounts of 1550 (and periodically thereafter) “la salle des caryatides.” Although these are not exact copies, they capture the essence of the Erechtheion maidens fairly well.

Despite the fact that there was no direct method of transmission of images from the original source on the Athenian Acropolis to the French and Italian workshops because there was no tourism to Greece to speak of in the sixteenth century, the term caryatid was nonetheless intimately linked to the maidens of the Erechtheion through the ancient copies extant in western Europe at this time. This example demonstrates that the Erechtheion maidens and the Vitruvian term caryatid were linked at least two centuries before the early modern travelers to Greece beheld these Athenian maidens in person and made what seemed at that point in time a sensible and logical connection.

The first reference to the Erechtheion maidens as "caryatids"

But can the explicit association of caryatid and the Erechtheion be pushed back even earlier? It is possible to argue that by the early Augustan period, the significance of the term mutulos to designate the associated Doric order had already been overlooked, and the maidens of the Erechtheion were considered the quintessential caryatids.

Before examining the evidence for this argument, it is crucial to discern what Vitruvius was actually referring to when he told his story about the humiliated Caryan women. Recent work on what Vitruvius probably had in mind when he proffered his etiology for the term caryatid has been done by Dorothy King (1998.275–89). She defines a caryatid as a female architectural support with one or both arms raised, wearing a polos on her head, and surmounted by an almost invariably Doric architrave.

Surviving examples of such true caryatids come almost exclusively from funerary or private contexts of the Hellenistic period, and are perhaps derived from a lost monument at Sparta called the Persian Stoa, described by Vitruvius immediately after his explanation of the term caryatid (1.1.6). For example, inside both the Sveshtari tomb in Bulgaria and a rock-cut circular tomb at Agia Triada on Rhodes, there are reliefs of women with one or both hands raised, wearing long robes, a polos on their heads, and with a Doric frieze above.

These Hellenistic Vitruvian caryatids appear to have been adapted to portray mourners, and almost always occur in funerary contexts. The other context in which Vitruvian caryatids appear is on a small scale in the private sphere of the elite. A good example—also found in a tomb—is a late republican cosmetics chest from Cumae into which little ivory “King-defined” Vitruvian caryatids with one or both arms up were inlaid.

Legacy of Vitruvius on the Erechtheion Maidens

Therefore, with the question of what Vitruvius was referring to by the term caryatid no longer dismissed as fantasy, it is now possible to examine the legacy of Vitruvius’s opening statements and see if the conflation of the term caryatid and the Erechtheion maidens can be pushed back to the Augustan period. To do this, it is crucial to remember that Vitruvius, in his definition of a caryatid, was describing a phenomenon of the Hellenistic period that was limited almost entirely to the private and sepulchral spheres of the elite, and so was not familiar to the general public.

As with Stuart and Revett, the very specific definition of caryatid with a mutule molding above was lost by the succeeding generations of architects who used de Architectura as a guide. Therefore, when a post-Vitruvian architect wanted to include female architectural supports in his design, what came to mind were not the reliefs in tombs and on cosmetic boxes, but the maidens of the south porch of the Erechtheion. The following monuments in Rome illustrate this phenomenon: the Agrippan Pantheon, the Forum of Augustus, the Forum of Trajan, and the Arch of Constantine.

Not long after Vitruvius wrote his treatise and dedicated it to Augustus as Imperator Caesar, major building projects in Rome were inaugurated by Agrippa and Augustus, namely, the Pantheon and the Forum of Augustus respectively. Both monuments incorporated female architectural supports on the Erechtheion model. It is important to remember that Augustus had recently won the Battle of Actium with Agrippa’s assistance, and afterward both men had spent some time in Athens.

The pre-Hadrianic Pantheon and the Tivoli maidens

Agrippa dedicated the Pantheon in the Campus Martius in 27 B.C., perhaps as the main victory monument in Rome that commemorated the Battle of Actium of 31 B.C. wherein Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra were defeated by Octavian/Augustus in an epic naval battle that resulted in Augustus being the sole ruler of Rome. The pre-Hadrianic phases of the Pantheon were also circular and, according to Pliny (HN 36.11), decorated with caryatids:

The Pantheon of Agrippa was embellished by Diogenes of Athens; and among the supporting members of this temple there are Caryatids that are almost in a class of their own and the same is true of the figures on the angles of the pediment, which are, however, not so well known because of their lofty position.

Pieter Broucke believes the Caryatids in the Agrippan Pantheon were quotations of the Erechtheion maidens and demonstrates convincingly that the four copies of Erechtheion maidens discovered in the Canopus at Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli in 1952 were probably rescued from the remains of the Agrippan and Domitianic Pantheons, most likely when the Pantheon was rebuilt on the same spot by Hadrian.

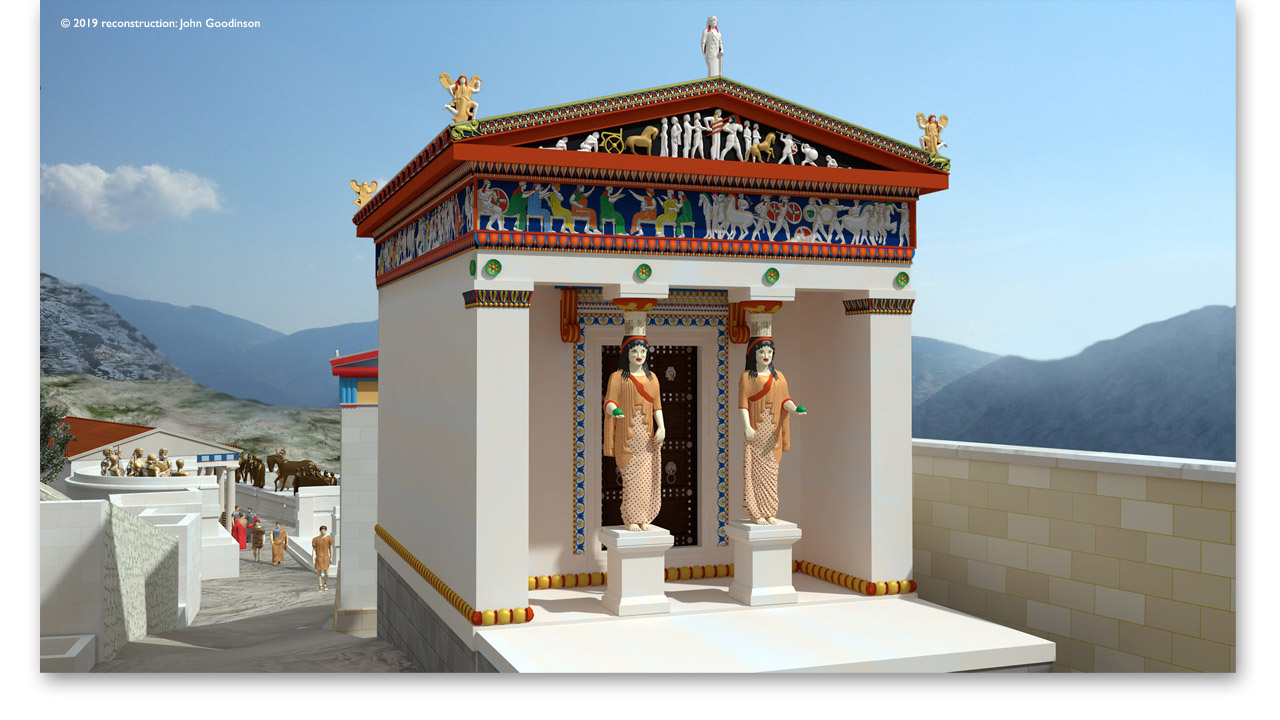

Tivoli maidens: Type A (Agrippan/Augustan) at left, Classical Erechtheion maiden from the British Museum in the middle, and Type B at right (Flavian). Photos by A Lesk, taken with permission.

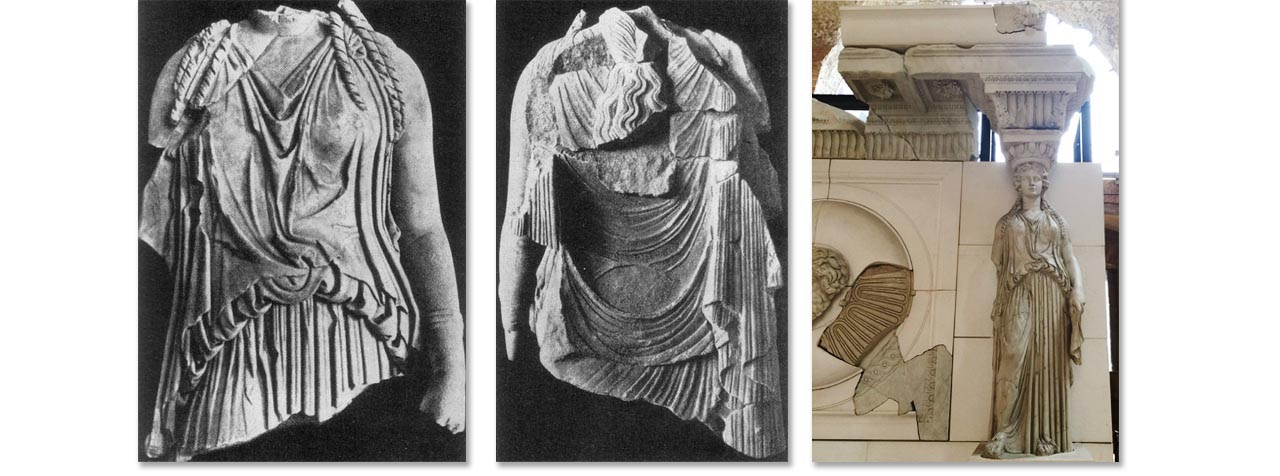

Broucke’s argument is as follows: the four Tivoli maidens can be divided into two types, Type A and Type B. Types A and B differ in significant ways: their height, the number of coiled tresses over their shoulders, the treatment of their footwear and drapery, the attachment of their capitals, and the profiles of their egg-and-dart and bead-and-reel moldings. Together, these features point to their production at different times by different workshops. Table 1 summarizes the features of the two types of Tivoli maidens, including Broucke’s conclusions regarding the dates of the copies, as well as a comparison of the features of the original maidens from the Erechtheion and the copies in the Forum of Augustus (see table below). As is clear in the table below, Type A is very similar to the copies of the Erechtheion maidens in the Forum of Augustus, especially with respect to the arrangement of the drapery in the vicinity of their stomachs. The match with the torso found in the Forum of Augustus is truly remarkable. It appears, therefore, that Type A dates to the Augustan period.

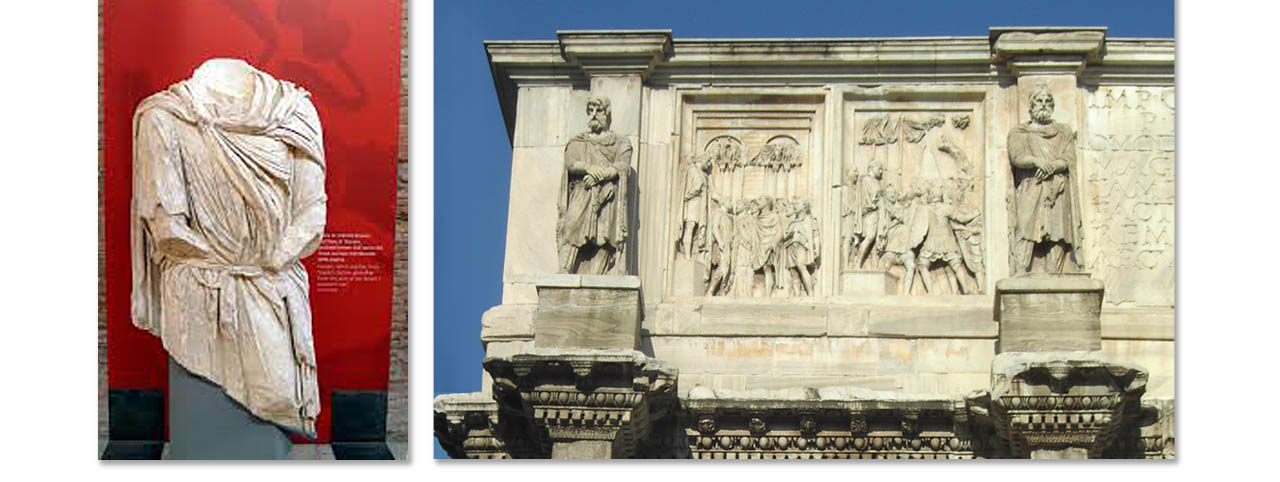

Below: Torso of maiden from the Forum of Augustus (compare to Tivoli type A) at left and in its reconstruction at right. Photo G. Stephens.

If Broucke’s theory is correct, and the Tivoli Type A maidens belong to the Pantheon, then they date to a few years before the Forum of Augustus and so served as the model for the Erechtheion maidens that appear repeatedly in the Forum’s attic storey. Type A may have been inspired by the Erechtheion maidens, but as the information summarized in the table below indicates, it is by no means an accurate quotation. We must remember that Pliny attributes the Pantheon caryatids to Diogenes of Athens.

Diogenes, as a sculptor and native of Athens, would have been very familiar with the Erechtheion maidens and thus able to recreate them within an acceptable degree of accuracy from memory. These Tivoli Type A maidens are the very sculptures Pliny must have seen when he says that they are in “a class of their own” in the mid first century A.D.

Type B, on the other hand, is a much more faithful quotation of the Erechtheion maidens. The arrangement of the drapery is almost identical, but the carving in general is not as well executed. The closest parallels for the drapery style are Flavian. Broucke 1998 characterizes the drapery as having “deep linear cuts” that “terminate abruptly,” having been drilled for accentuation.

Furthermore, the chronology of the Tivoli maidens corresponds well to the known phases of the pre-Hadrianic Pantheon, namely the Augustan and Domitianic periods. So, if Broucke is correct in his identification of the caryatids of the first-century b.c. and a.d. phases of the Pantheon as the copies of the Erechtheion maidens found at Tivoli, and Pliny used the term caryatid in the second half of the first century a.d. to refer to these very sculptures, then the implication for the interpretation of Vitruvius’s legacy is very clear: Pliny, one of the best educated and lettered men of his time, called, by way of copies in the Pantheon, the maidens of the Erechtheion "caryatids." This connection supports the argument that when writers or architects after Vitruvius envisioned caryatids—at least after the 70s A.D. —they made the mental connection with the famous maidens from the classical Erechtheion and not with the rather obscure funerary phenomenon of the Hellenistic period.

The Forum of Augustus

Having established the impact of Vitruvius on the interpretation of the Erechtheion maidens in the first century, we can now turn to the contexts in which these human architectural supports are found. His vow on the eve of the Battle of Philippi in 42 b.c. no doubt burning in his conscience after defeating Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium, Augustus ensured that progress was being made on the Temple of Mars Ultor and his Forum by the mid 20s B.C. The design of the Forum included an attic storey above the colonnades with Erechtheion maidens alternating with clipei, or shields, adorned with heads (figure 8 - chart above. Reconstruction below)

Only two types of these heads survive, those of Zeus Amon and a Gaul. These heads represent the proud nations conquered by Augustus and the emperor’s hegemony in both east and west. This interpretation is underscored by the inscribed lists of conquered people that were on display in the Forum. The Forum of Augustus as a whole sent a message of the new emperor’s wide-ranging control over the growing empire by means of its sculptural program and use of multi-colored marbles from Egypt to Asia Minor.

The copies of the Erechtheion maidens are usually interpreted as references to the glory of classical Athens—as a parallel to the golden age of Rome inaugurated by Augustus—because many modern scholars wish to repudiate Vitruvius’s story. Lily Ross Taylor (1949) more subtly interprets the inclusion of the maidens in Augustan monuments as distinctly anti-Antony and indicating Rome’s superiority over Greece. For Taylor, the Erechtheion maidens were something beautiful that could be imported from an otherwise debased culture. While the equation with Periclean Athens may have been intended on one level, the maidens must be considered in their symbolic juxtaposition to the alternating shields of conquered nations.

Alongside the fact that Athens had sided yet again with the losing party in the Battle of Actium—and had to grovel for forgiveness in the aftermath of the civil war—these maidens of classical Athens had become symbols of submission, true caryatids in the eyes of the visitor to the Augustan Forum. It is also worth remembering that Augustus had never been well-disposed towards Athens. Therefore, the Erechtheion maidens would have been an appropriate signifier of Athens’ (and Greece’s) subjection to Roman rule.

Related Roman monuments - Forum of Trajan and Arch of Constantine

Further evidence for interpreting the copies of the Erechtheion maidens in the Forum of Augustus with Vitruvian overtones derives from two later and related monuments: the Forum of Trajan and the Arch of Constantine. Statues of bound Dacian prisoners carved in purple-veined marble occupied the identical position in the Forum of Trajan as the copies of the Erechtheion maidens did in the Forum of Augustus. This highly visible architectural parallel between the two monuments leaves no doubt that the two sets of statues in the attic storeys were equated as symbols of victory over conquered peoples.

Forum of Trajan captive at left and Arch of Constantine with Trajanic captives reused as spolia at right. Labeled for reuse.

Moreover, that icon of spolia, the Arch of Constantine, recycles eight Dacian prisoners very similar to those found in the Forum of Trajan. Again, they are set up in the attic storey and frame recycled and recarved relief panels with scenes of successful army activities from the lost arch of Marcus Aurelius, thus serving as constant reminders of the fate and circumstances of a conquered people. In fact, beginning in the Renaissance, these Dacian captives were actually considered to be quotations from the Persian Stoa at Sparta described by Vitruvius (1.1.6) and illustrated as the masculine counterpart to the caryatids of the Palladian edition.

Conclusion

In sum, using a contextualized diachronic approach to analyze the problem of Vitruvius’s definition of the term caryatid and how this relates to the Erechtheion maidens, we have observed that upon the publication of de Architectura, the Erechtheion maidens became a part of the Roman iconographic vocabulary of triumph. Therefore, from the early Augustan period through the fourth century A.D., the maidens from the Erechtheion at Athens represented for the viewer caryatids in the Vitruvian sense: symbols of submission and humiliation.

And finally, why did Vitruvius choose the story of the Caryan women as the prime example of how to explain an architect’s design choices to his patron for the opening passages of his treatise? At the time of writing, the war with Persia was still playing itself out for the Romans. Sulla and Pompey’s victories in the east were overshadowed by the loss of the military standards by Crassus in 53 B.C. to Parthia. Perhaps Vitruvius’s inclusion of the anti-Persian story is his reaction (as a military engineer under Julius Caesar) to the smarting memory of this humiliation, a story that would have pleased Augustus to whom the treatise was addressed.

Its subtext also served as a warning to those cities, mostly in Greece and Asia Minor, whose monuments Vitruvius held up as key examples of the architectural phenomena he was describing: do not consider medizing like the Caryans did during the Persian War or else Rome will punish you! As an extension of Vitruvius’s political intention, because the Erechtheion maidens in the Forum of Augustus were interpreted as caryatids by the Roman audience, perhaps their inclusion in the iconographic program can be seen as a morality tale, reflective of the new social and military order of Augustan Rome.

The duality in the use of the Erechtheion maidens—to emulate classical Athens while at the same time commemorate its defeat—is paralleled in the complexity of Augustus’s commemoration of the Battle of Actium and the problem posed by celebrating victory in civil war within Rome itself. Furthermore, Augustus’s employment of idealized Greek females, a style he also applied to the portrayal of his own female family members in monuments such as the Ara Pacis, and the new legislation regarding the position of women in Augustan Rome demonstrate another dimension of this duality: the copies of the Erechtheion maidens in Rome were idealized, generalized, and placed in contexts of subservience.

In conclusion, this examination of the Roman reception of the Erechtheion illustrates how the temple and its sculpture played an important role in the psyche of the people of the Roman empire, particularly at Rome. The new way of looking at Vitruvius presented here serves to clarify some of the previous misconceptions about his text’s relationship with the Erechtheion. It demonstrates how, almost from the moment his definition of caryatid was written down, every generation until now has interpreted the term in almost exactly the same way, namely, as referring to the constantly visible maidens of the south porch of the Erechtheion and as eternal symbols of submission and humiliation.