The ancient religious centre of Delphi, which encompassed the most renowned of all oracles, was established in an imposing, awe-inspiring natural landscape, surrounded by the foothills of Mount Parnassos and overlooking the sacred valley that stretched down to the shore of the Corinthian Gulf. Although the site was inhabited as early as in the second millennium BC, its evolution into a place of worship and divine consultation - interlaced with geological properties-- was destined to be the object of discussion and admiration throughout the centuries.

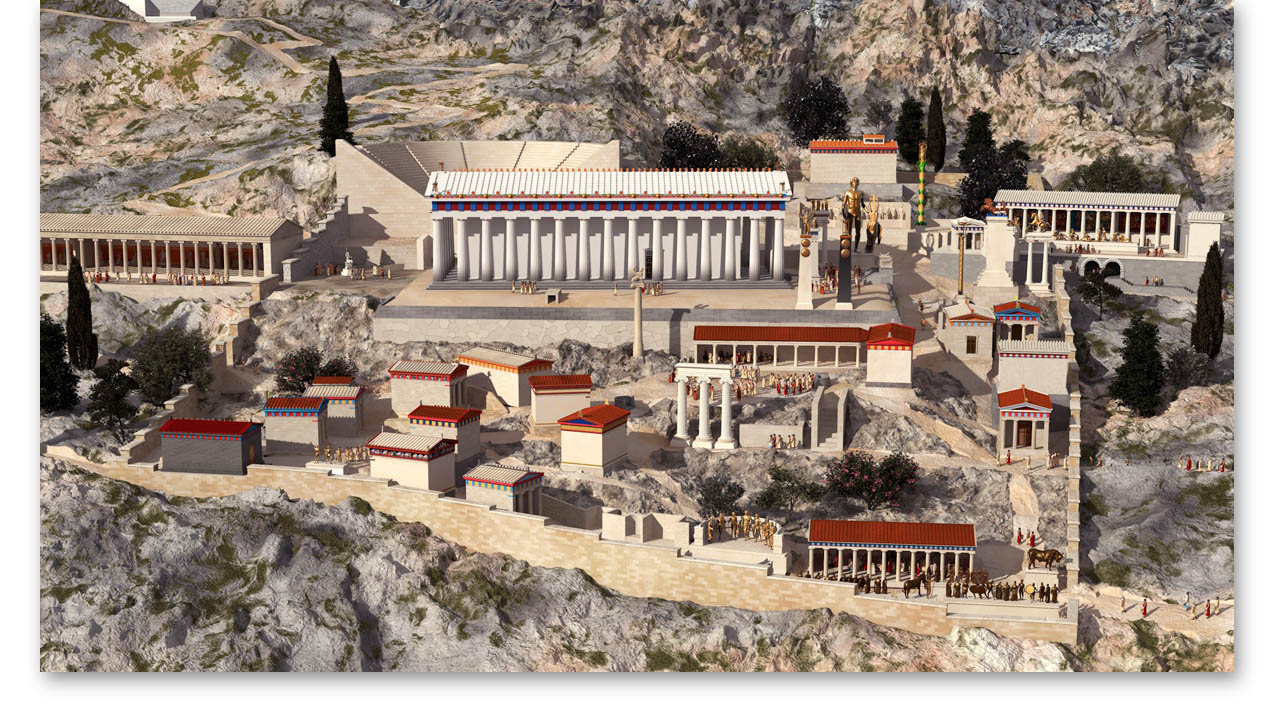

Numerous monuments of diverse plan and form, grandiose temples, porticos of various proportions, elaborate fountains, statues carved in marble or cast in bronze and others of gold and ivory furnished the two sanctuaries at Delphi. The upper one, of Apollo, dominates the slope; although crowded with votive offerings, its well-arranged layout, in successive artificial terraces accessed through nine gates at different levels, is in balance with the landscape.

Most of the monuments commemorated historic events or victories in the battlefield, others reflected the prestigious status of certain poleis or kingdoms, while others were driven by athletic championship or piety. Gratitude for the gods’ intervention in the mundane domain might be too simplistic a justification for the great many offerings. We would, instead, interpret them as legacies of the respective city-states who commissioned the dedication.

Above: 3D reconstruction of the sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi. @2020. Model: John Goodinson. Scientific advisor: Professor Elena C. Partida.

The sacred processional way, a ceremonial path, defined the backbone of the sanctuary, flanked by statuary groups (some on columnar supports), niches and treasuries (architectural dedications rather than buildings for the deposition of gifts). Wall-paintings decorated the interior of the Cnidian Lesche, a hall for social or philosophical discourse, whereas stone friezes sculpted in relief and narrating mythological scenes decorated the exterior walls of treasuries. Unique is the musical notation of hymns to Apollo, engraved on the walls of the Athenian treasury. Every architectural order and style was represented in the two sanctuaries at Delphi. Apart from the poros stone imported from the northeast Peloponnese, and the locally quarried fine limestone, white marble from the Aegean islands and from Mount Pentelicon met the demands of building and sculptural programs. The commissioners spared neither the cost nor the labour.

Unique is the musical notation of hymns to Apollo, engraved on the walls of the Athenian treasury. Every architectural order and style was represented in the two sanctuaries at Delphi. Apart from the poros stone imported from the northeast Peloponnese, and the locally quarried fine limestone, white marble from the Aegean islands and from Mount Pentelicon met the demands of building and sculptural programs. The commissioners spared neither the cost nor the labour.

The radiance of the oracle spread across the ancient world. All the different regional traditions represented here reflect precisely the dissemination of the site’s reputation. Eastern potentates, such as Croesus of Lydia, sought prophecies and rewarded the god with luxurious offerings. Pharaoh Amasis of Egypt is said to have contributed with funds for the reconstruction of the temple, after a ravaging fire. The temple of Apollo is a fine example of Doric architecture. A succession of temples were erected on this spot, at the heart of the sanctuary, on a terrace contained by two retaining-walls running almost parallel to each other.

The southern one, constructed of polygonal stones with curved joints, was covered in inscriptions – testimonies of the manumission of slaves before the eyes of Apollo. These freedmen would never again be enslaved. The legendary adyton, the sanctum where the process of divination took place, occupied part of the deepest level of the temple. Access was allowed only to priests who would decipher the words spoken by Pythia, the prophet-woman who directly received Apollo’s response.

But this divine place did not see only acts of reverence, rituals and sacrifices. The heart of the sanctuary was beating faster during the Pythian Games and other festivals, when athletes, actors and musicians, ambassadors and pilgrims flocked to Delphi from all over the world to participate or simply to attend. Drama and rhetoric performances, music and choral contests were held in the theatre, whereas athletic competitions were held in the stadium, which can be classified among the best preserved ones. With a total seating capacity for 7,000 spectators and a monumental triumphal entrance in the form of a triple arch (funded by the benefactor Herodes Atticus), the Delphi stadium offers an interesting variation in the design of athletic installations.

The applause of champions by masses of spectators in such a sacred ambience made their distinction even more meaningful and worthy. Although they often dedicated their prize to the god, the most precious award to bring back to their homeland was the praises and glory.

Training and preparation for the games took place in the Gymnasium, also in an excellent state of preservation, with all typical components: a peristyle court lined with rooms (palaestra) for the wrestling bout, a roofed portico for exercising in inclement weather, a circular pool and bathing facilities. Hot baths (thermae) were installed here during the Roman period.

Dedicated to Apollo’s sister, the “lower sanctuary” of Athena Pronaia features a totally different layout and setting. Two temples framed the tholos -a round edifice of supreme artistry but uncertain function- beside two ornate treasuries. The one in Aeolic order represents an elegant dedication made by the city of Marseilles.

The valley of Pleistos, an extensive grove of several thousand olive-trees, stretching south of the sanctuary until it meets the sea, is unbreakably related to the history of the site. Its boundaries almost coincide with those of the ancient ‘sacred land’ consecrated to Apollo and reserved for pasture, as decreed by the Delphi priesthood and the Amphictyony. Cities adjacent to the valley often asserted its management or exploitation, thus triggering the outbreak of the so-called Sacred Wars.

Today, however, as we contemplate the calm spaciousness in the shade of the Phaedriades (peaks of Parnassos range), waiting for the sun to rise above them, the green and blue horizons blend. Barely can we make out the silhouette of Apollo, accompanied by a bunch of Cretans, ascending towards the place where, through the allegory of his prophecies, he would teach people the value of thinking, the assets of philosophy. He would instruct them to whet their spirit, to live in harmony, to study arts and music, and always to ensure that the law and order prevail over anarchy and chaos.